Confessions of a Recovering “Imposter”

Opening and Closing The Door of Doubt

I don’t remember the exact day or time I became intimately familiar with “Imposter Syndrome,” but I know with certainty what I was doing. I had just finished a speaking engagement in front of a large audience. There was applause, and people approached me to talk after the event. That’s when I heard the very first whisper of a voice I had never heard before…

”You aren’t who they think you are.”

This was many years ago, and those voices have largely been silenced, but with time comes great understanding, insight, and an enhanced sense of perspective. I now have a much better grasp of why I was about to endure a string of years with impostor syndrome, which became a routine part of my professional existence.

Before doing significant public speaking, I was a high-functioning senior professional (Creative Director/UX lead, etc.) and was very good at what I did. But I worked exceptionally hard, and it did not come quickly. I learned (often the hard way) how to best motivate teams. I worked tirelessly to understand client needs and exceed expectations, and I also worked in earnest to contribute to the culture of the firms I worked at. Making “the case” for the output of my teams and getting clients on board could be challenging and sometimes nerve-wracking. One of the clients in my early career years had a reputation for making our team members cry.

”This is arduous work,” I remember thinking, yet by that same measure—I took pride in the work and the teams I led because it was it was never easy.

But getting on stage for the first time—well, I am probably not the norm here—didn’t feel half as challenging as presenting work in some of the boardrooms I have been in. An audience doesn’t intimidate me, and it feels natural for me to speak in a public setting. It’s not like I don’t put effort into my talks—quite the opposite, especially when you factor in that I do my own slides and do not have an executive support team doing any heavy lifting for me. I work diligently to prepare for a talk.

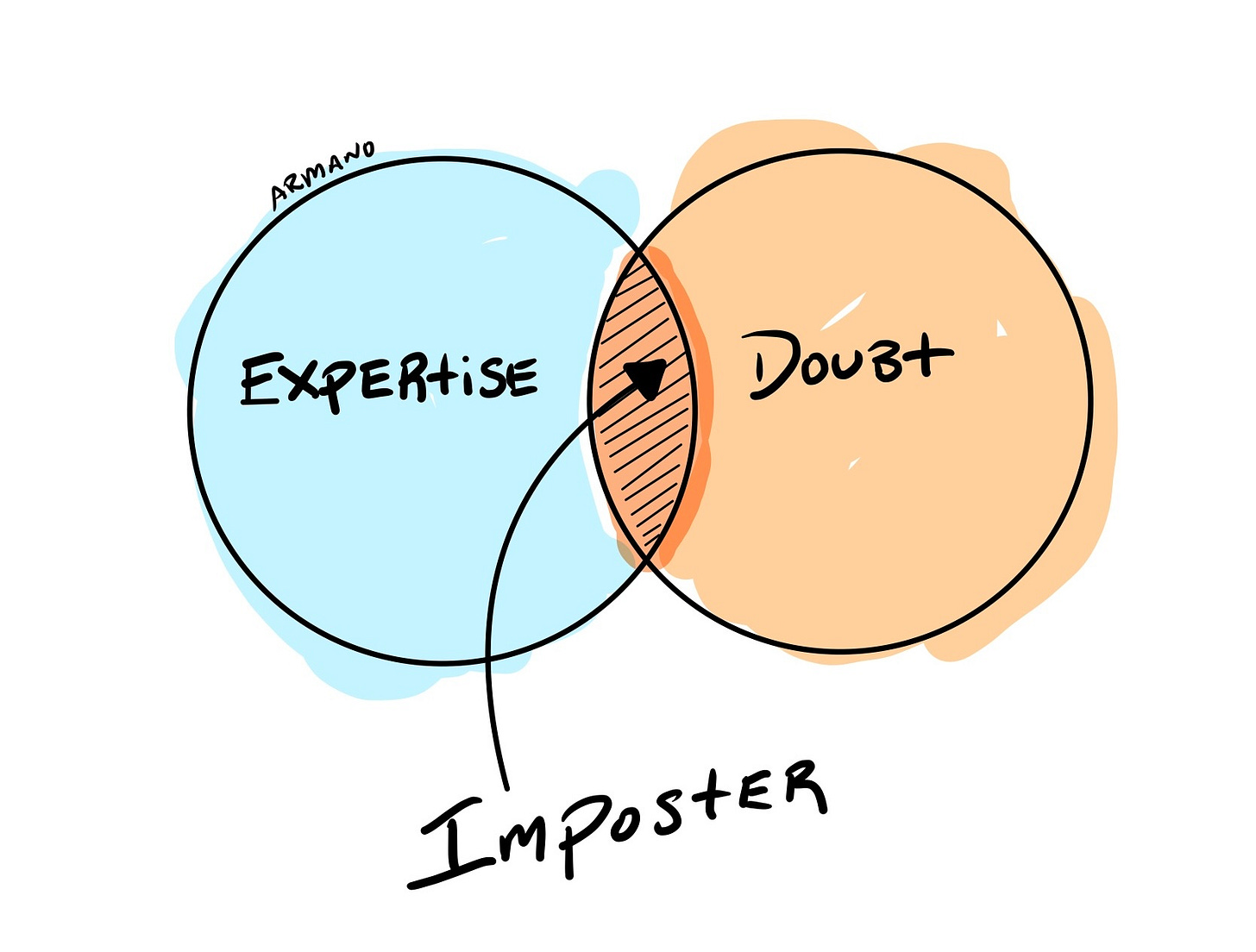

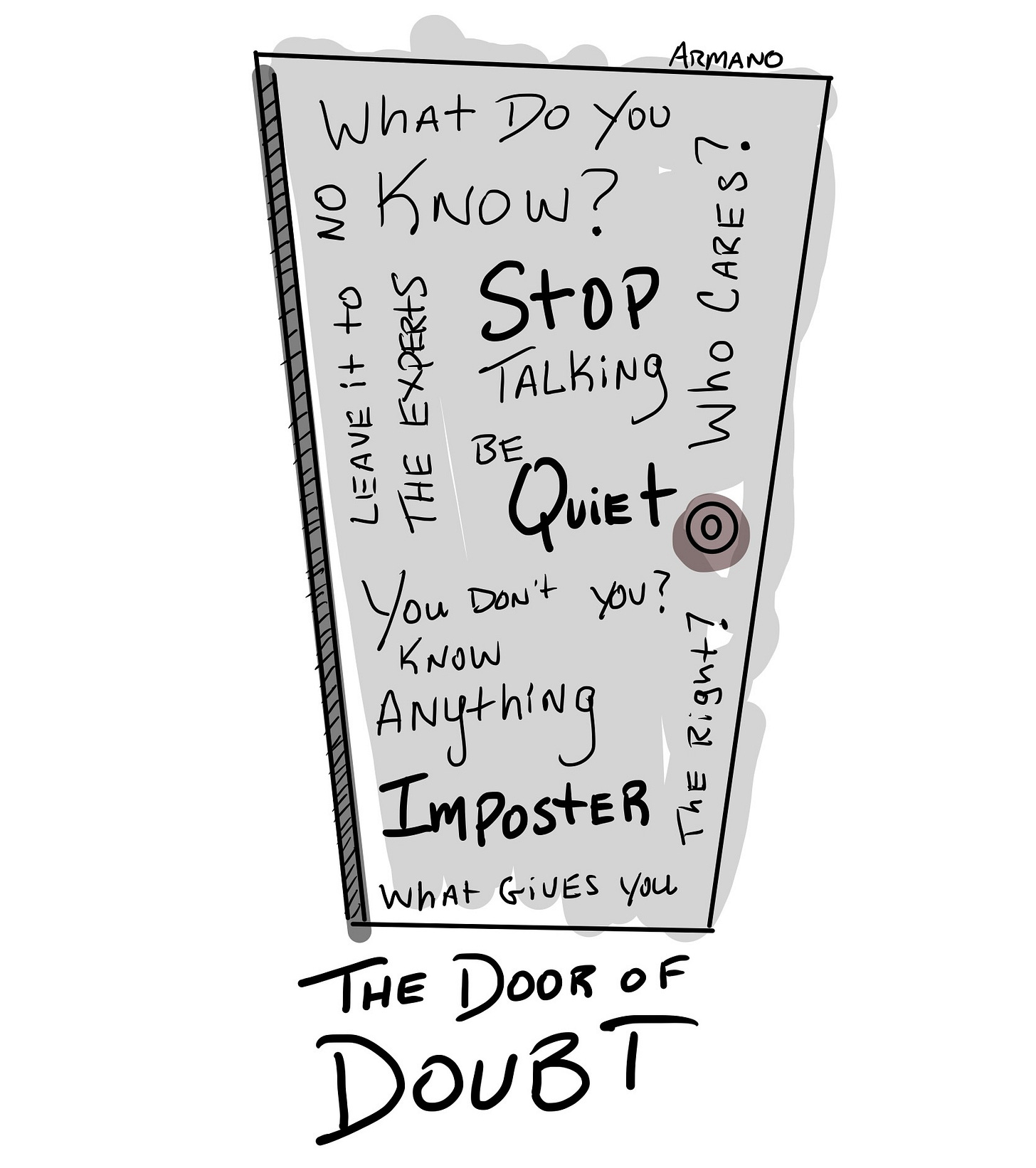

But the talk itself does not feel insurmountable. For me, public speaking is essentially storytelling with a crowd in the background. The better story you can tell, the better speaker you are. I discovered that I was a pretty good storyteller, but I was at odds with myself because, unlike my client or company work, I often told stories about what other people were doing. And I questioned the value of telling stories about other people's actions vs. only talking about my direct efforts and fruits. And at this very moment, when I devalued the thing that other people were finding value in—this when I opened wide the door of doubt…

As I mentioned earlier, I closed the door of doubt some time ago—probably well over a decade. I no longer hear the internal whispers of impersonation I once did and know I have nothing to prove. But with hindsight being 20/20, I want to share a few confessions of some of those whispers in the hopes that if you ever hear them as well, we can choose not to open the door to doubt and stop them sooner rather than later.

”Who Cares”?

Believe me, if you find yourself on a stage, many people care. They are the ones who put you there. This whisper is especially nonsensical as it flies in the face of what got you an audience. It’s a foolish whisper; we don’t need to suffer fools.

”You Don’t Know Anything”

Again, this whisper makes zero sense. Chances are you know many things—you don’t know everything because nobody does. You know enough and have earned the right to share it. What’s on us is that we have a responsibility to do it memorably.

”Leave It To The Experts”

Self-denial that we have expertise that is worth sharing and worth something often comes from within. The inner impostor, which really doesn’t exist, wants us to believe that our expertise is worth less than or not on par with others. Again, the audience decides/validates this, not our inner imposter.

”Stop Talking/Be Quiet”

This one… oh boy, this one. During my time living and working with impostor syndrome, there were a handful of moments where I became quiet, faded back, and felt I didn’t have a right to talk. Those are the moments when we permit the inner impostor to take over. That’s how we know the door of doubt needs to close for good.

Public speaking or any activity that could trigger or activate our inner impostor means we've got a generally good human quality—humility. But the adage, “too much of a good thing,” rings true here, and the whispers of an inner imposter can take hold when a generally decent human quality turns into something else that holds back our growth and development.

If, like me, you’ve opened that doubtful door at some point, and maybe as you read this, feel it remains open, take comfort knowing that it can be closed as quickly as it is opened.

Fantastic self reflection thanks for sharing.